By Helena Worthen, helenaworthen@gmail.com

In this e-mail interview, Helena Worthen engages in a conversation with the “Old Vygotskian,” Định Lê Thiên, founder of Gia Môn Sen Sáng Learning Center in Phan Rang, Vietnam.

Some Historical and Cultural Background

In the interview that follows, Định Lê Thiên describes the Gia Môn Sen Sáng Centre in Phan Rang, Vietnam. Foreign readers will ask, “If this is an alternative after-school program, what is it alternative to?”

To answer that question we have to talk about where the education system of Vietnam stands now in terms of its development. Vietnam was a colony of France since the 1880’s; its harbors were ports of trade and its industry was rubber plantations where workers were effectively enslaved; the population was 95% illiterate and its French education system was what Gail Paradise calls “obscurantist,” saying it “…condemned the nation to extinction” (Paradise 2000 p. 19). The French left in 1954 after defeat at Dien Ben Phu and the United States took over in the South. In 1975, at the end of what we in the United States call the Vietnam War, re-unified Vietnam still had ten years of war ahead with China and the Pol Pot regime in Cambodia.

Nevertheless, during this time the government created a national school system, one year at a time. This included vast campaigns against illiteracy, building schools, training teachers and creating materials including textbooks. Resources were desperately limited. For example, it was not until 1993 that there were new textbooks all the way through into the 12th grade (Hac 1998 p 21). But as a socialist country and part of the world community of socialist countries, the works of Soviet psychologists like Vygotsky, Luria and Leontief and educators like Makarenko would have flowed naturally to Vietnam through people who had studied in Russia and other socialist countries. So the new Vietnamese education system in the 1980s and 1990s was designed by people who were educated with the theories of Vygotsky and with Marxist philosophy, and those materials were available.

In 1986 Vietnam started a program called doi moi or “renovation,” designed to allow foreign investment and personal accumulation of capital by Vietnamese for the purpose of investment. Here is a summary of doi moi that both states what it is and demonstrates the difficulty of describing it:. “…a new model of a market economy with a socialist orientation has been formulated and is becoming more and more visible through actual practice….Initial fruits of the renovation programmme reflect the great potential of the Vietnamese economy once it transferred to a multi-sectoral commodity economy that is driven by market mechanisms with the control of the state” (Quy and Sloper 32).

In 1992, as part of doi moi, a vast plan for the national system of education was produced with the assistance of the United Nations agencies (Hạc,1994, p 20-34; MOET, UNDP, UNESCO 1992). By this time the Soviet Union had been dismantled and socialist countries were having to find their own way to face the global economy. This plan, which is still being followed in its basic outline today, was created by mostly Vietnamese educators under the leadership of Phạm Minh Hạc, First Vice Minister of Education and Training, who had studied in Moscow at Lenin University and received his doctorate from Lomonosov University (Moscow University) under Alexander Luria. It was necessarily a highly centralized system, which is also a nationalist point of pride.

Four years later, in 1996, diplomatic relations with the United States were restored. This meant trade with the US was resumed. This might explain why, on his first attempt to search for books about education, Định Lê Thiênfound Dewey, Montessori and Piaget, in English, rather than the works of Vygotsky and other Soviet writers, and why the Soviet books had gone out of print and were only available second hand on the internet. Part of this shift was the replacement of Russian and Chinese as the languages of academia and trade, with English, the dominant “foreign” language today.

The education system in Vietnam is still all one system, centrally regulated although private schools and universities are allowed. The offices that regulate the system are separate from the schools. Marxism-Leninism and Ho Chi Minh Thought are a required percent of the curriculum all the way through. The system is exam-driven. One exam, a national exam, based on the national curriculum using multiple-choice questions (except for the literature section) (VietnamnetGlobal) determines whether a student graduates from high school and also what college or university they will be entitled to apply to.

From my own experience teaching at Ton Duc Thang in Ho Chi Minh City, I can report that the Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) has an active presence on campus in determining curriculum, textbooks, testing and grading down to the level of what is going on in each classroom. Unfortunately, as we in the United States are well aware, one consequence of a rigid, high-stakes approach is that there are inevitably both incentives and opportunities for cheating, from top to bottom. When Định Lê Thiên talks about “the corrupted path” I believe that this is what he is referring to.

The “corrupted path” goes beyond cheating, of course. As the Vietnamese economy expands, the two primary investments families make are a nice house and education for their children. Students and their families experience intense stress and anxiety as they approach exams which will determine what rank of university they will be allowed to apply to, or whether they will be able to apply at all. Today, a BA is essential if a young person wants to get an office job as compared to a job in manufacturing (garments, leather, electronics, etc.) or the service industry (food or hospitality). More serious than cheating, therefore, as Định explains, is the kind of fear that forms a barrier between students and teachers and makes it nearly impossible for students to have honest, critical conversations with their teachers. This fear then affects the kinds of discussions that can take place in a classroom, the kinds of responses students can make to assignments, and creates the so-called “shy” or “lazy” student that we, and colleagues at our university and others, recognized as only too typical.

In the interview, Định describes the current form of Vietnamese education as both “feudal” and “bureaucratic.” He says:

These characteristics continue to this day. They form a downward, sinking path for both teachers and students. That path of education created old people in a new era. Therefore, to create something new, it is necessary to create a school that avoids that path.

Định’s Vygotskian experiment, in other words, is both something new and a return to the past, but under different conditions. One might call it a “correction.”

Interview with Định Lê Thiên, The “Old Vư-gốt-xki-an”

Between 2015 and 2019 my partner Joe Berry and myself taught labor studies to undergraduates at a university in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. My approach to labor studies is to treat it as adult education for social justice and use the theories of learning that originated with Vygotsky in the 1920s in Russia. Through contacts via the Marxist Internet Archive we met a young woman, Sally Uyen Mju, who told us that she knew “an Old Vygotskian” who ran his own school in another city about 7 hours north. Expecting to meet an old man who had perhaps studied in the Soviet Union and carried Vygotsky back to socialist Vietnam, we asked if we could meet him. Sally agreed, made arrangements, and took us to Phan Rang, where we met an intense 29-year old who, with his brother and sister-in-law, had gathered some 60 students together for a before-and-after school learning program built on the basis of Vygotsky and Makarenko’s ideas.

It so happened that at the same time, we were participating electronically in a conference in the US called “RE-Generating CHAT,” sponsored by the Spencer Foundation. One of the goals of the conference was to surface what had become of CHAT, the most recent (in the US) name for Cultural-Historical Activity Theory, the current incarnation of Vygotskian tradition. The “Old Vygotskian,” who was in fact a very young Vygotskian, seemed to be a living example of how this tradition had persisted on the other side of the world in a country where Marxism is the official philosophy.

What follows is an email interview with the “Old Vygotskian,” Định Lê Thiên, founder of Gia Môn Sen Sáng Learning Center in Phan Rang, Vietnam. After our visit, I sent Định a list of questions as a way of continuing our conversation. Định’s responses were originally written in Vietnamese and then translated into English by Sally Uyen Mju. While Định and Sally were working on the responses, I tried to answer as many of my own questions as I could by reading what was available in the U.C. Berkeley library about the history of education in Vietnam. A summary of what I learned that way is in the sidebar.

In early May 2019 I sent the edited text of this interview back to Định for his edits and comments. This draft includes his responses to that draft.

Định takes up from the middle of our conversation in Phan Rang, which had to shift into email at the end of our visit there in March:

From: Định Lê Thiên <djnh.ltd@gmail.com>

March 21, 2019

Hello, Helena and others who join this conversation. I will divide my answers to Helena’s questions into 5 topics: First, Makarenko and Vygotsky; then Pham Minh Hac and Vygotsky’s propaganda; applying Vygotsky’s ideas to transform “passive and lazy” students, the CC system, and lastly information about how the Gia Môn Sen Sáng centre operates.

Helena: You said that your reading of Makarenko was an early step in the process leading to your decision to open your own school. You say that he led you to Vygotsky; how did that happen?

Định: I think there is a misunderstanding here. I need to clarify what I wrote in the first in a paragraph of my previous email: “Makarenko led me to the path to Vygotsky.” I was writing too briefly. In the book I have, Makarenko did not mention Vygotsky, nor did Vygotsky mention Makarenko. I mean that reading Makarenko helped me understand Vygotsky.

This is a long story. I will write some more details to explain why I said “Makarenko led me to the path to Vygotsky.” My path to become an educator can be divided into 2 stages. Stage 1 is when I was in Ho Chi Minh City. I started to research and read about many philosophies and methods of education. Stage 2 is when I decided go back to Phan Rang and test Makarenko and Vygotsky. More specifically: When I was in Ho Chi Minh City, I worked as a tutor for living and taught children in a volunteer house for free.

Helena: By “volunteer house” do you mean a program where teachers volunteer their time to teach children?

Định: They are volunteer teachers, they teach without salary. So, teachers are not stable for a long time, they also worry about their livelihood. It was also the time in Vietnam when there was an influx of books about education. I bought quite a lot of books, although my income at this time was not much: Montessori, Jean Piaget, John Dewey …

Helena: These are writers who are well-known in Europe and the US, so it sounds as if you were reading mainstream US education materials.

Định:. In this volunteer class, children only learned Math and Vietnamese. They lacked other basic knowledge. So I and my colleagues, the volunteers I contacted on Facebook, started to teach the students about science, and we applied Montessori. More specifically we used the book Montessori Today: A Comprehensive Approach to Education from Birth to Adulthood, by Paula Polk Lillard.

I also made toys like this:

To complete this problem, students have to fit the corresponding blocks correctly into the concave spaces. They can check it themselves to see if they are doing it right or wrong. When the picture is completed, they will comment on what this chart means. Once they understand the meaning, they can work without blocks.

Here is another form:

My teaching aids were very simple, they took a lot of time to make, and they were difficult to preserve and very perishable. I did not have enough money to make them with better materials.

Then I realized that if I wanted to apply Montessori’s ideas to older students, there would be some limitations. I would need more space and an environment in which children could be more active. Otherwise it would be impossible to escape the corrupted educational path.

Helena: What do you mean by “the corrupted educational path”?.

Định: The current status of education in Vietnam is influenced by the past. Vietnam used to be a feudal country. Feudal education had three characteristics: First, it put too much burden on grades. It viewed passing examinations as the purpose of learning. Passing examinations meant you could become a boss, have a position in society, and get power and money. Second, it had a very bureaucratic administration. Third, students were forced to memorize everything, without understanding it. Everything the teacher said, students had to copy and memorize – all of it. These characteristics of feudal education continue to this day. They form a downward, sinking path for both teachers and students. That path of education created old people in a new era. Therefore, to create something new, it is necessary to create a school that avoids that path.

So I think I needed to find another way. At that time, I also discovered the silent flow of Soviet education. These books are not being republished. They can only be found in online bookstores that sell old books.

Helena: That phrase also needs explanation. When I read that sentence – “the silent flow of Soviet education” – I was startled. Does this mean that by the time you are looking for good materials on education in the 2010’s, the legacy of Soviet psychology and education theory has become a “silent flow?” By this time the foreign languages of academia were no longer Chinese and Russian; they had become English. It is possible that once diplomatic relations were opened with the US in 1996, English-language materials flooded the market, Dewey was available but Vygotsky was not.

Định: Before 1991, there was Soviet support for Vietnam during the war. As part of the alliance relationship between the two countries, Vietnam sent students to the Soviet Union to study. Therefore, Vietnamese psychology books were mostly translated from Russian. Vietnam’s psychology groundwork affected Soviet psychology. After 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed, Soviet psychology books were no longer reprinted in VietNam. People would no longer see the works of Vygotsky, Makarenko, and others on Vietnamese bookshelves anymore, even today. The moment I bought old Soviet books, I was very surprised, and felt “the silent flow of Soviet education” that continues through these old books.

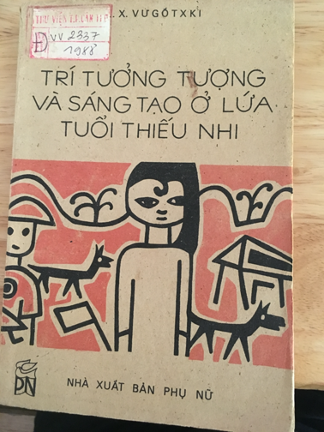

An “old book,” Imagination and Creativity in Childhood. Apparently de-accessioned from the Can Tho University library.

Another “old book”: Vygotsky, L.S. The Psychology of Art

https://www.marxists.org/archive/vygotsky/works/1925/

Once I had these books, I read about Vygotsky and learned about the ZPD. I was still a tutor at this point. I applied the ZPD to lectures and exercises for students and discovered that it helped them to gradually approach difficult lessons. At this time, that was all – only that. I did not know anything deeper. Then I read the book The Road to Lifeby Makarenko. The book provided me with experiences I had never had before. I really liked the idea of a self-governing student community. And more specifically, I liked the way the experience of the community changed the personality of children. But why did it do that? Then I re-read Vygotsky and understood it more deeply. I linked the two documents myself. This one supported that one.

I realized that the personality of the child changes because it is influenced by the environment in which they live. Through the process of collective labor and discipline, children impact the environment around them while it in turn reforms the child’s psychology. So that is why I said “Makarenko led me to the path to Vygotsky.” Because when I read Makarenko, it helped me understand Vygotsky more. That’s just my subjective feeling

Then came Stage 2. I really wanted to practice what I learned. But the conditions in Ho Chi Minh City would not allow me to do that: no money; no classroom, not enough teaching aids for the large number of students. There is no money to make better teaching aids. Also, no one has any power to change what goes on in volunteer schools. Finally, it is very difficult for a new program to fit in with the educational program in Vietnam where grades are so important and decide everything. Under these conditions, there would be no change at all. So in 2015 I went back to Phan Rang city. This is when I actually tested Makarenko and Vygotsky. I started with only 3 students. Gradually there were more.

Because of the educational context in Vietnam, at first students came to me to get more knowledge and skills to finish their tests in school. So anything other than that, from the perspective of parents and students, was just for fun. Fun is good, children need fun to be motivated and active. But just fun is not enough. The activities the children were doing are also a ZPD, to help children gradually adapt to society. Projects implemented by students must have specific outcomes. Students need to know how to plan, organize and assign tasks, how to proceed according to deadlines, how to have a serious working mind, always thinking of improving productivity, improving oneself. And most importantly, to think about the collective and the weak.

Let me continue to explain. Why did I need Makarenko in those early years to understand Vygotsky?

Vygotsky said about imagination: “The first type of association between imagination and reality stems from the fact that everything the imagination creates is always based on elements taken from reality, from a person’s previous experience.” (Note: This is on page 13 of Imagination and Creativity in Childhood.) I studied the theory of education the same way: read the theory and compare it with reality, or experience. Maybe we will practice. Maybe we will observe the object of the study. Or we will make a comparison based on our experience.

I had never had the social experience of organizing collective labor so I did not understand the importance of the collective in impacting and changing a person’s personality. Nevertheless, when I read The Road to Life by Makarenko, I imagined a lively community and entered into it. I felt as if I had turned it into my own experience, in order to understand Vygotsky’s theory.

However, I could not adopt Makarenko’s theory entirely because of some basic differences:

| Makarenko’s camp | My centre | |

| Purpose | Children live there and work there. And work for food. | They come to study, then they go home. They come just to study knowledge, to learn study skills for solving exercises, and to get better grades. |

| Time fund | Chlidren lived all the time in the camp | They come only when they need to study. They have 270 minutes per week for a subject. |

The lack of time is the thing that makes me suffer the most. I wanted to create a culture, which needs to be handed down from generation to generation. This includes ways of living, ways of working, ways of behaving. Individuals who misbehave will gradually learn the way of the collective, understand how this collective is living and know how to work for the collective. But since our model is just a center, there are some limitations that can’t be helped. We will take a long time to create a culture. Then, once created, it is difficult to maintain that culture. This is partly due to the instability of students during school time; after all, they can quit school if their parents see low scores.

Here is one way we are creating a community of students. When the child approaches a new problem, they need guidance and encouragement to do things at a higher level. In my centre, all the students — everyone including the teacher – have to guide others. Students with more experience will guide the student with less experience. Multi-age students interact with each other to create a student community. This community links students together to make projects. Besides, they share with each other many things: such as romance, family stories, study habits. Because the spirit that the center wants to aim at is to create a community like a family, a home. The spirit is in our centre’s name: “ Gia Môn Sen Sáng”.

Our center has a lot of activities like what you saw on your visit, thanks to some students spending most of their time here. In fact, they spend more time here than in their homes, and much more than students do at other schools. We needed only 10 core students and we have created something different from other schools Phan Rang city.

Even today I still read Makarenko to consult his views on collective labor and student management skills to build my center.

As for your question about why I chose Vygotsky. First, I chose Marx’s philosophy to guide my thinking. I wanted to focus on activities and interactions between people and the real world. I recognized the role of the collective and the role of people in the collective. I realized that research about people is not only about studying the components that make up people, but also about people placed in social contexts. At this point, I found that Vygotsky’s psychology has a depth that I had not fully understood.

Helena: The second day of our visit we came back to see the collection of books that you have. One book in particular, the one with the orange cover and the library stamps on the outside, struck me like an arrow. I saw the children’s drawings in the back pages, as fresh as if they had just been drawn by the hand of a child this morning. Then, when we got back to Ho Chi Minh City on March 10, Sally sent me the English translation of that book. It’s on the Marxist Internet Archive website (Imagination and Creativity in Childhood, Vygotsky 1927). As I read it, I felt again a sweeping feeling of recognition, of liberation, much like the feeling I had when I first read Vygotsky back in the early 1960s. Vygotsky writes so clearly and his metaphors are so precise.

I have to ask you about Phạm Minh Hạc. The translator of at least two of the books you had was Phạm Minh Hạc. He not only was Minister of Education in Vietnam from 1987-1991 but he received his doctorate in Moscow, studying with Luria, who had been a colleague of Vygotsky. You know Phạm Minh Hạc as the person who translated Vygotsky and the edited collection of materials you showed us — another one of the precious “old books.” So we know that he was one of the people who brought Vygotsky to Viet Nam. Apparently in the late 1970s he was already making translations to be used in schools or by teachers. Then there is the Vygotsky book about childhood creativity published by what appears to be a publishing house dedicated to women.

Định: There is a misunderstanding here. Pham Minh Hac did not translate Vygotsky’s book Imagination and Creativity in Childhood. Duy Lap is the translator of that book. Hac’s works of translation are in the form of an article about Vygotsky. There are also books in which he summarizes his understanding of Vygotsky, and he translated Luria and Leontiev.

The reason why Women’s Publishing House published books about Vygotsky is beyond my understanding. I asked my friend who works there. He said, “I think it does not have any particular significance. However, books that belong to the category of educational psychology can be published by any publishing house. In the 80’s, every publishing house was racing to publish as much as possible.” So, the fact that a book was published by Women’s Publishing House may not carry a deep intention at all.

Helena: In my readings about the history of Vietnamese education, I learned something that I will insert even though I only learned it while we were revising this interview. I got this from reading the National Plan of Action on Education for All (draft, in the UC Berkeley Library), 1992-2000 (Hanoi 1992). Maybe that book would have been one designed for the education of parents and teachers of children. After all, in the late 1980s there was still illiteracy in Vietnam, so you could not count on parents being able to teach children. This would have been during the time when Phạm Minh Hạc was Minister of Education and during the early days of doi moi, or re-novation, the transition from a bureaucratic, centralized economy to the current socialist-oriented market economy. A short selection from this report gives a sense of the challenge facing the education system: “In the disadvantage areas, bamboo and thatched-roof houses as class-rooms still make up a high portion. Another difficulty is a shortage of text-books, only 45% of school children have a full set of text-books and 95% have text-books of the 2 main majors.” P. 4 (original text). Nonetheless, “text-books and teaching material have been actively prepared, such as those guiding activities in the family-based child groups and those for educating parents. In 1990, there were 180,000 parents who received knowledge on child care.” (P 2).

I wanted to mention this because it is important for us in the United States to learn that a book like this might have well been part of an official program of national education project at that time.

But you were talking about whether students today in Vietnam study Vygotsky.

Định: I spoke to my friend, Nguyen Bao Trung, a lecturer at the Ha Noi Pedagogical University and learned from him that education students do study Vygotsky. However, he added, “The way they teach Vygotsky is just a peek around the corner, some simple and trivial content. Students don’t understand Vygotsky’s ideas properly. They can’t see his logic, they don’t see any application of his ideas. In Vietnam, no one is qualified to teach students to understand the greatness and genius of Vygotsky.” I understand this, because looking on the internet, I can see that the number and quality of articles and dissertations applying Vygotsky in Vietnam is poor. How sad! The bad attitude toward academic research and its implementation does not just apply to Vygotsky. It also applies to many other scholars. Educational theories were brought into Vietnam as a trend but then went away. Only the approaches which could be successful in opening a school still remain, like Montessori, Reggio, or Steiner.

When our center chose Vygotsky’s theory to become our core theory, we needed to have good resources. My students and I are trying to translate Vygotsky. This friend, Nguyen Bao Trang, is helping us with Mind in Society, the collection of Vygotsky essays edited by Michael Cole. It is being translated by our students and teachers, with editing and checking support from Nguyen Bao Trung. He also wants to raise up the study of Vygotsky but his time is limited. He also has other projects to finish about Freud and Lacan.

Up to now I only read Vygotsky through Phạm Minh Hạc’s understanding. So sometimes, I didn’t know all about his genius. There are a lot problems raised by Vygotsky that I can’t understand. But I have chosen him so I will follow him, his ideas. So that is why we decided to translate Vygotsky’s work and the people who writing about Vygotsky. One part of this will be used for research materials of the center. One part will be used to spread Vygotsky, creating interest and encouraging serious research by many people. This is a very long way.

Why did we wait until now to translate Vygotsky? I really wanted to do this sooner, but my English is not good. Only now do we have enough personnel. We have an English teacher. She is very good and has experience as a team leader. The number of students is also higher than in previous years, so we have more choices to set up translation groups. We have academic and editing support from Nguyen Bao Trung.

Helena: By explaining the roots of creativity in concrete, simple language Vygotsky frees teachers and students from the fear of having the wrong idea or making a mistake. This may be especially important in Vietnam where, in my short experience of teaching here (three visits, ranging from 6 months to 12 weeks, at undergraduate university level) I have had to learn the terms “shy” and “lazy” to describe students who are not “active.” My current tentative explanation of this is that these students are in fact scared, because since early childhood they have been subjected to a regime of memorization and tests. Even the teachers, who have been raised in this culture, seem scared. They pass this along to their students in the way they follow the curriculum that has been given to them and prepare students for exams. So they have to learn despite an atmosphere of fear.

There is also something going on that is worse than being “shy” or “lazy” or “afraid.” It is what happens when students are so worried about their scores that they will cheat. Of course, since I am teaching in English through translation, it is only by accident that I find out if students cheat. But both the incentives and opportunities for cheating are tremendous. From what I have seen, this applies from the bottom to the top.

Định: Yet on your visit to the Gia Môn Sen Sáng Center you saw that our students are energetic, cheerful, and actively raising their hands to express their opinions and argue with each other.

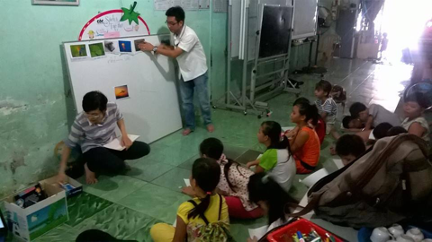

Helena: Yes – after we made our presentation that evening, students stood up right away and asked excellent questions, and then when Joe asked them a question – “Why are most of the boys sitting on one side of the room and girls on the other?” – they started arguing with each other and laughing out loud. I could hardly believe my eyes. I have a photograph of this moment that I took while it was happening:

Active students arguing and laughing at each other at Gia Môn Sen Sáng , March 2019

Định: Meanwhile, the students that you interacted with at your university were timid and shy. Why? I think the problem is in the relationship between the study environment and teachers. The environment in which children learn and work affects and improves their psychology. The following comparison table shows how this works:

| Gia Mon Sen Sang Centre | Public school |

| Teachers are friendly with students. We don’t consider ourselves to be higher than students. We played with them, ate and talked like friends, brothers and sisters in a family. | Teachers have a higher position than students. Therefore it is very rare to have a good conversation between students and teachers. |

| Students who come here are always feel comfortable like being at home, often laughing and joking. Teasing teachers seems like their hobby. | “Teasing a teacher” is almost a banned situation in public schools. It is very hard for students to talk to teachers at public schools. |

| Students have the right to choose to participate or refuse. Teachers encourage children to participate in activities. Many students who started in the center were very shy, but after being encouraged, they gradually adapted, joined, and enjoyed activities. | Students are forced to participate in activities, participate in school movements because of emulation scores and achievement of the class. |

Helena: This matches my experience. One year the university provided us with a private office. Some students came to talk with us there privately, and we learned a great deal from them that we would never have learned without that privacy and we made friends with those students.

Định: Now I will talk about applying Vygotsky’s ideas in actual exercises. The idea is that we go through action to form thoughts. First, students interact with the teaching aids to solve problems. They use the theory and thereby understand it. Starting with practical activities, their intuition gradually transfers to abstract activities in the brain. Later, students will solve problems instinctively when they encounter an equation and there is no need to use these teaching aids anymore.

Take for example learning math, solving first-order equations: How to use the rule to change the mathematical sign. Some students were thinking too slowly so I made some cards for students to practice with. I wrote a number on in each card, a variable, a plus sign and minus sign. When it switches to an equal sign they use the pen to edit the sign of the card.

I took these pictures in 2015, when I returned to Phan Rang. (Below is the fourth in a sequence.)

Helena: One of the students at the Gia Môn Sen Sáng Center gave me a square card covered with plastic on which was printed “1 CC”. Can you explain what this is for? What do students do with it? I hope that this question will lead you to describe more about how the students themselves run the school. I think that one of your teachers told me that the students clean the school, wash the floors, etc. themselves.

Định: That card is a CC. This is the “CC system.” CC is a short form of the term “ Cubic centimeter,” which is the unit for measuring volume using the cubic centimeter. We usually use it to measure a volume of blood. So CC means the sweat and blood of the worker. A CC is the reward that students receive after working. CC is like money in society. When they create new projects, or participate in existing projects, they will receive a salary of CC. But CC can only be used in the centre.

The CC has 3 denominations. Each card has a different sentence written on it. Par value (Note: “par value” means face value) of 1cc comes with the sentence: You work, you enjoy. The par value of 2cc comes with the sentence: Got disciplined, got successful. The par value of 5 cc comes with the sentence: Got creativity, got a step forward. On the back of each card is the slogan of the center: Work to become a person.

Why CC was born? My purpose is to provide students with the things the need to enter society. I had to create a zone of proximal development for the students to gradually adapt and understand how society works. I realized that the monetary system plays an important role in the functioning of society. In one way or another, so many of the relationships between people, the skills of working and negotiating contracts involve money. So I created a monetary system that simulated the money system.

CC can only be used in the centre. There are some services are only compensated with CCs. There are other services that accept either CC or real money, depending on what students choose. A service using CC may be provided by the center or by students.

“Services provided by students” are services created by students. They usually rely on the facilities of the center. Students will pay CC fees for these services. For example, the centre has one IT room. In the IT room, student Pham Thai Bao has opened an IT class to teach other students typing on the computer, how to use Word and PowerPoint. In exchange, students will pay Bao their CC as a fee for this service. Here are some services that you can buy using CC: A Wifi password, time to use the computer, learning about robots, learning English online communication, learning programming, learning IT, and cooking and eating together at the centre at the end of the month. The services do not stop with the list above. More will be added, depending on the financial situation of the center. Our next plan is to open a gym. The library room will charge CC. Poor students (students from low-income families) have the opportunity to study at the centre through trying to work for CC and registering in courses.

There is also a CC market where we don’t intervene: there is buying and selling CC on the black market. These are the personal transactions of the students. Some of them have CC and want to sell for money. Some of them do not have CC but want to use a service so they need to buy CCs.

To have CCs, students have to work. There are many different jobs and different purposes. These jobs are activities based on student’s willingness and excitement. For example, student Le Hoang Yen Nhi is planning that this summer that she will teach the poor (low-income) elementary pupils for free. She will find friends who have similar interests. Then they will design their teaching programs with our oversight. We will give her CCs to pay a salary for her and for her friends.

Jobs can be a career experience, to help children understand more about themselves, and help them choose future careers. For example, student Le Yen Nhi wants to be an MC in the future. She has joined Radio 789 with the 11thgrade group to be a reporter. Her entire crew are all students. Another job is to hold a review class for every student, or create their own project and call on their friends to do it. For example, student Pham Thai Bao will help the other students with Physics exercises. She will not receive money; she will only receive CC.

Some jobs are contracted and bid between groups. For example, chores. This includes cleaning the classroom. Two or three groups of students may want to bid. Each group will send a leader and write how many CCs they want to have this job for a week. The group with the lowest CC will get the contract. This form of bidding leads to many interesting lessons later on.

We teach lessons about labor through CC because it creates a miniature society. This includes how to work in groups, connect with friends, organize work, manage and plan, how to bravely propose ideas and convince friends to do it, how to set up payroll, take time attendance, recruit personnel, negotiate wages and pay wages by CC.

Because CC is like money in society, students begin to understand how society works. They learn why there are a lot of people who don’t do anything but still earn CC. They learn when and how to go on strike to ask for more CC (an interesting story). They learn that the more important the job they do, the harder they will be to replace. Someone whose job is easily replaced by others will earn less CC. That is called the labor market. They learn about competition among groups when they are bidding. And then groups join together, avoiding price pressure. We do experiments on how to create a community of employment agreements among members. There are many and many lessons.

Helena: Finally, can you put in writing some details about how you manage the school? You have three full-time teachers plus two assistant teachers. Also, sometimes students act as teachers. You charge a fee but you have some scholarship money.

Định: This is the organizational structure of the Gia Mon Sen Sang centre. At the beginning, I alone taught and experimented. Three years later, my younger brother and my sister in law come here and to teach together. We established the fundamentals to build the center. Today, I teach mathematics, my brother, Mr Đạt, teaches Physics and Chemistry and my sister-in-law, Mrs. Thu, teaches English; she is concurrently doing management. My mother, Mrs Phú, is the administrator, she collects tuition fees and handles relations with students’ parents. We are still looking for and recruiting more teachers.

With regard to collecting tuition fees and expenses: during my time in Ho Chi Minh City, I realized that in order for anything to develop sustainably, there has to be a stable financial source. We cannot rely on outside funding. Only collecting tuition can solve this. The collection of fees like this is normal in the context of Vietnamese education.

Our expenses include: The salary for employees: Teachers, lecturers and administrator. We are equipped with air conditioning and television. (In Phan Rang, not every class is equipped like us.) We have regular expenses: pens, ink, electricity and water. We have expenses for activities: for example, we have to buy tools to support the children to implement radio projects. (And these devices are quite expensive). We have irregular expenses such as buying tables and chairs, boards and we have to fix them if they are broken. We need to buy books to add to the library. (The library used to operate, however, it was stopped. We are waiting for a student to accept the bid and develop a reading culture. Then the library will open again. During that time, I have continued buying more books for the library – good, expensive books.) We also have to save money to rebuild the center and add more spacious rooms, rooms that are beautifully designed and more modern.

Here is how we support our students. To change the life of a poor child, we can grant scholarships so that they can go to school. However, it is not enough. I used to work with poor children with free education. But they just consider it as a kindness and they just enjoyed it. Not much changed. In order for a child to escape poverty, the important thing is the will to take care of themselves and the skills learned through labor. I help them by creating an active environment and encouraging them to work. The rest depends on them. They will decide whether or not they will join projects to get CC and use it to pay for the courses.

We do not give scholarships to poor (low income) students, nor to students with good grades. We offer scholarships to students who have changed themselves in a positive way and have contributed to the collective, who are important and positive seeds in social change.

Here are some of the difficulties we have encountered. We cannot change the content of our teaching because we depend on the curriculum of the public school. We are currently just a center; we can only improve part of the learning content. We have not yet developed strong social media, so many students and parents do not know about our approach. Many parents still prohibit their children from participating in activities. We pay our salaries after we have covered the costs for our facilities, so our salaries are quite low. It depends very much on the number of students we have.

But here are our plans for future development. We are translating Vygotsky’s books and other authors using Vygotsky’s theory in order to do research and find ways to apply Vygotsky in a deeper way, whether is preparing lectures to organizing activities, shaping psychological development and young personalities. We are rebuilding the access roadmap, noting the steps to be done, the policies and objectives at each level of the labor programs. We are training teachers. They need solid professional knowledge, and the flexibility to create steps when students are slow and cannot catch up to the lesson. Ultimately, all these will converge and we will be able to establish a school.

Only by establishing a school can we fully apply our understanding of Vygotsky. I observed that Montessori succeeded in part because she established many kindergartens, and let many people set up kindergartens according to her standards. A doctrine has only a solid foundation when it is formalized into schools and embodied in the actual things needed to operate the school.

About Helena Worthen

Helena Worthen is an author and activist, and a former professor at the National Labor College and professor of Labor Studies at the University of Illinois. Her recent works include What Did You Learn at Work Today? Forbidden Lessons of Labor Education, of which there is a review published here. You can read more about her and her ongoing work at https://helenaworthen.net

References

Kelly, Gail Paradise. 2000. French Colonial Education: Essays on Vietnam and West Africa. Edited by David H. Kelly.AMS Press, New York, NY.

Ministry of Education and Training, Government of Viet Nam; United Nations Development Programme; United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organisation. 30 September 1992. VIE/89/022. Report of the Viet Nam Education and Human Resources Sector Analysis.Volume 1, Final Report. Phạm Minh Hạc, National Project Director, Hanoi

Makarenko, Anton. Available at https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/makarenko/works/road1/index.html (Accessed May 17, 2019)

Ministry of Education and Training, Socialist Republic of Vietnam. 1994. Education in Vietnam: Situation, Issues, Policies. Pham Minh Hac, Editor in Chief. Hanoi.

Phạm Minh Hạc, 1998. Vietnam’s Education: The Current Position and Future Prospects. Hanoi, VN: The Gioi Publishers

Sloper, David and Le Thac Can, Editors. 1995. Higher Education in Vietnam: Change and Response. Chapter 2, Nguyen Duy Quy and David Sloper: Socio-Economic Background of Higher Education since 1986. St Martin’s Press, NY

No Author, VietnamnetGlobal. Cheating Scandals in Northern Provinces to be Reported at National Assembly (NA) https://vietnamnet.vn/en/society/cheating-scandals-in-northern-provinces-to-be-reported-at-na-525242.html Accessed May 7, 2019.