By Anna Harris & John Harris

It started with a blurry little cherry tomato catching the overhead light during a video call. It did so in such a way that it gave the tomato two eyes. My dad (John) was holding the tomato to the screen, keeping my three-year-old (Bastian) amused with fruits and vegetables that were lying on the kitchen table nearby.

Our calls were becoming more frequent and playful during the pandemic. Bastian was also becoming excited about cooking, as he helped us prepare meals at home, and he loved asking my parents to turn their camera so he could watch them cook their evening meal in Australia, as we had just finished our breakfast in the Netherlands.

“Tommy!” – my son shouted delightedly – “Tommy Tomato!” And so the adventures of Tommy Tomato were born, a comic strip my dad created for his four grandchildren, detailing the cosmic adventures of the tomatonaut Tommy. They were sent every couple of days in email instalments, as Tommy made his way from Mars to earth and back again.

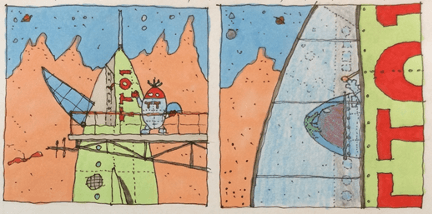

Scenes from inside TTO1, The Adventures of Tommy Tomato and Friends, by John Harris

Children are often said to be very good at creating imaginary worlds to escape to, a great skill to have during quarantines imposed by an infectious outbreak. As Erin Maglaque (2020) writes in her wonderful review of the book Florence Under Siege: Surviving Plague in an Early Modern City, “to learn what in meant to survive [in a pandemic], we might do better to observe …. the teenage sisters who danced their way through the plague year.” But adults can be good at dancing, playing and inventing escapes too. It did not go unnoticed that Tommy was leaving his home into the galaxy, while being confined in his rocket ship at the same time. A following spin-off series my dad created, about a mouse in a submarine, followed the same theme of exploring the world within a small (to me claustrophobic) machine.

There were other spin-offs too. One day, my son asked if we could make Tommy’s rocket ship, while we were playing around with papier-mâché. The digital and physical became further entangled, something Marije Nouwen and Bieke Zaman from the MintLab in Leuven, Belgium, have explored by looking at the multi-sensual nature of technologically-supported intergenerational play with dislocated grandchildren.

I had been thinking about and with papier-mâché as part of a project I work on with others in Maastricht, in the Netherlands. The project looks at the materials of medical education (Making Clinical Sense). There is a long tradition of making anatomical models from papier-mâché, as well as models in other scientific disciplines. I was trying to remember, from my childhood memories, how to make the stuff.

TT01 by Anna and Bastian Harris

This was in many ways my own idea of play, not Bastian’s. I was having great fun playing with him and thinking about my research topic, crossing the boundaries of work/life we are meant to keep separate. We made a rocket ship from a used toilet roll, flour and water glue, and old newspapers. It was fun but perhaps what I learned most from making the rocket was the way in which he created worlds around the tomato and the rocket, teaching me his own idea of play.

Meal times introduced many stories about the tomatoes – poor Tommy got eaten a lot! The rocket was zoomed around the house, stopping for fuel on chairs and tables, picking up various passengers, doing things I could never have imagined. On a walk outside, we stopped at a closed café and my son told me that the closed umbrella on a concrete stand was his rocket ship, and the other umbrella was mine. Wobbling on the concrete base, Bastian informed me that his rocket had a piano, a bathtub, a playground, a ball, tomatoes, his friends, a library, two cafes, and some flowers in it. These details soon found their way into my Dad’s Tommy Tomato instalments. The digital and the physical world became entangled; the illustrations, video calls, fruits and mashed paper.

Scenes from inside TTO1, The Adventures of Tommy Tomato and Friends, by John Harris

How can we learn more, as adults, and specifically as researchers, from this kind of play? The early childhood researchers Ana Stetsenko and Pi-Chun Grace Ho (2015) write,

In play, children might be closer to reality than we may think: not to reality how it is, but to how it could be, as an open-ended possibility in which our quest for freedom in the world shared with others is supported and actualized … We all, as educators and scholars and simply as adults, have much to learn from children’s play—about the world as it can be and about how much needs to be improved in its status quo if we want to be free and relational at the same time.

(p. 233, my own emphasis)

Was my father tapping into this, in his drawings of the mouse and the tomato in their confined spaces of the rocket ship and submarine? Were these creatures escaping the COVID-19 realities, adventuring into spaces and places of unknown possibility?

Renowned for her celebration of play in academia, the critical feminist theorist Donna Haraway suggests that, as scholars, we also need to develop practices for thinking about forms of activity which are not “caught by functionality, those which propose the possible-but-not-yet, or that which is non-yet but still open” (Weigel, 2019). But taking play seriously is difficult for scholars, who often have to justify their methodologies and stake claims of seriousness. I am always reminded of this in collaborations, such as with Valentijn Byvanck, from the art museum Marres House for Contemporary Culture in Maastricht, who tries to take academics out of their comfort zones, in playful encounters with the public. Psychiatrist Paul Ramchandani and his colleagues, whose academic work on play (funded by Lego) highlights the importance of play in early childhood education describes it as having the characteristics of “fun, uncertainty, challenge, flexibility and non-productivity” (Kelsey et al., pre-print). All of these characteristics are challenged in academic environments where fun is used for ice-breaking, uncertainty and flexibility are squashed in funding proposals and ethics applications, and non-peer-reviewed, accountable productivity abhorred.

In the 1930s, the Dutch historian and cultural theorist Johan Huizinga (1938/2014) wrote a book – Homo Ludens – about the importance of play in cultural life. In the book, Huizinga describes play as free and fun, though necessarily separate from “real” or “ordinary” life. This suggests my son and Dad’s play is indeed an “escape” from the home and a pandemic, and from other elements of everyday life. But what if we also saw the video-mediated play between the two of them as intermingling the ordinary and extraordinary, of everyday life and the “possible-but-not-yet”? I think the latter might offer us, scholars, more productive inroads into play and ways to embrace play in our work.

Ramchandani’s current work involves looking at the mitigating effects of play on the impact of quarantine and related restrictions on children’s and young people’s health and education. Ramchandani’s team’s protocol acknowledges that “amidst the uncertainty and social isolation that can accompany quarantine and/or pandemic circumstances, adult-initiated/directed play and joint play with adults may be more common than usual” (Graber et al., in press). This is certainly what I experienced, but I also realize that I have much to learn from my son, and from my father, about play in imaginative worlds. It also makes me wonder how we might introduce this more playful mode into scholarly work.

In our research team, Making Clinical Sense, we have experimented with many different playful modes of learning about our topic of enquiry – medical education. This includes sensory experiments both before and during fieldwork. Before fieldwork, we hired a kitchen and conducted a proof-of-concept methodological study using photography, video and drawing to observe a sensory skill being learned (omelette making) (Harris, Wojcik, & Allison, 2020). During fieldwork, we crafted weekly exercises together – what we called probes – such as making collages and standing on tabletops to observe the local specificities of our field sites. We have conducted academic workshops which explored the materiality of learning through hands-on activities involving making clay dwellings in the grounds of our workshop venue, and have engage with embodied processes of learning and thinking together using overhead projectors, circuit boards, and napkin folding (Craddock & Harris, 2020). In our own faculty, we created, along with our collaborators, a workshop exploring learning spaces using simple materials such as plasticine, wool and Lego (Harris, Sumartojo, & Wyatt, 2020) to remake our local workplaces. The workshops worked best when people were freed from the need to be productive, when they were offered prompts to escape logical lines of thinking, and when they were given time to throw themselves into the fun of mucking around with materials.

Since the goal of our Making Clinical Sense project is not only to explore the materiality of medical education historically and ethnographically across sites, but also to collaborate and learn closely alongside medical educators and students, we have also crafted workshops together with fieldwork collaborators. Using similar materials as in our other workshops – plasticine and wool and Styrofoam balls, things you might buy at a simple craft or toy store – we facilitate the time and space for medical teachers to play and tinker. They do this anyway in their work, and in fact our workshop aims mostly to highlight the creativity and improvisation that is at play in our field sites everyday. The teachers immersed themselves in these playful engagements with making teaching tools, which was in the end immensely insightful when it came to understanding more about the materiality of objects used in educational settings. Why materials, such as papier-mâché, may work better for some lessons, for example, than others.

In the future, I would like to try and engage in more open-ended methodological experiments that have an “underwater” or “extra-terrestrial” feel, of further escape and open-ended possibility, for it seems to be this is where we can learn not only about the not-yet, but about ordinary life too, and question the status quo.

About the Authors

Anna Harris first worked as a doctor in Australia and the UK before learning anthropology and turning her ethnographic gaze back to the medical profession. Missing the hands-on element of clinical practice in academia, her work endeavors to find creative, fun and practically engaging methods for studying questions of embodiment, learning, materiality and infrastructures of medical practice. She currently works as an Associate Professor, with a great team of anthropologists and historians, at Maastricht University on the Making Clinical Sense project.

Project website: www.makingclinicalsense.com/

Personal website: https://annaroseharris.wordpress.com/

Video about Anna’s work: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yInwPlIEbTg&list=LL

John Harris is a retired architect living in Tasmania, Australia. He has worked on projects throughout Australia, Asia, North America and the Middle East. During his almost fifty years in the profession, his tools of trade were pencils, ink and coloured pencils, only venturing into computer aided design later in his career. The Tommy Tomato series, created for his grandchildren during novel coronavirus isolation, has reacquainted John with his enjoyment for hand drawing, a skill almost lost in the days of computer technology. The cartoons have not only initiated a fun way to engage with his grandchildren, but have been a source of personal entertainment during the lockdown.

Acknowledgements

Anna’s research has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program (grant agreement No. 678390). She would like to thank Thomas Fuller, Loraine Harris, and the other members of the Making Clinical Sense team for their feedback on an earlier draft of this essay, and Ivana Guarrasi, for seeing the potential in this idea, and for the wonderful suggestions for how to develop it.

References

Craddock, Paul, & Anna Harris. (2020). Workshopping: Exploring the entanglement of sites, tools, and bodily possibilities in an academic gathering. Journal of Embodied Research, 3(1), 2 (16:17).

Harris, Anna, Andrea Wojcik & Rachel Vaden Allison (2020) How to make an omelette: A sensory experiment in team ethnography. Qualitative Research, Early Online, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1468794119890543

Harris, Anna, Shanti Sumartojo & Sally Wyatt, (2020) “Designing for atmospheres of learning”, https://fasos-research.nl/fasos-teachingblog/2020/01/15/designing-for-atmospheres-of-learning/, accessed 17th June 2020

Huizinga, Johan (2014). Homo Ludens: A Study of the Play-Element in Culture. Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing (originally published in Dutch in 1938)

Graber, Kelsey, Elizabeth Byrne, Emily Goodacre, Natalie Kirby, Krishna Kulkarni, Christine O’Farrelly, and Paul Ramchandani (pre-print), A rapid review of the impact of quarantine and restricted environments on children’s play and health outcomes. Accessed 17th June 2020 from https://www.activematters.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Play-in-the-Pandemic-Rapid-Review.pdf

Maglaque, Erin (2020) Inclined to putrefaction, London Review of Books, 20th February.

Stetsenko, Anna, & Pi-Chun Grace. Ho (2015). The serious joy and the joyful work of play: Children becoming agentive actors in co-authoring themselves and their world through play. International Journal of Early Childhood, 47(2), 221–234.

Weigel, Moira (2019) Interview: Feminist cyborg scholar Donna Haraway: ‘The disorder of our era isn’t necessary’. Appeared in The Guardian 20th June: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/jun/20/donna-haraway-interview-cyborg-manifesto-post-truth

Wojcik, Andrea, Rachel Vaden Allison & Anna Harris (2020) Bumbling along together: Producing collaborative fieldnotes, In Fieldnotes in Qualitative Education and Social Science Research: Approaches, Practices, and Ethical Considerations,edited by Casey Burkholder and Jennifer Thompson, Routledge, New York

Thoroughly enjoyable article with many good examples of collaborative creativity between

adults and children during pretend play. For Vygotsky pretend play was important as a way to develop skills in reading, writing, and art, but we can add math, science, and computer literacy. Tommy the Tomato’s adventures both in outer space and under the sea could lead even further to such educational activities for the child. Then there are the immediate benefits of maintaining social interactions,emotional self-expression, and even metaphoric thinking (the umbrellas as rocket ships). Thank You for sharing this article!