This paper was constructed with a critical race theoretical lens and centered on storytelling as a legitimate intellectual, methodological tool. As an African-American, a descendant of enslaved Africans, my cultural experience in this country is rooted in this particular and peculiar phenomenon. This paper provides an overview of theoretical considerations for the relationship between morality, racial justice, and psychological research. Three articles were selected for a close examination of these relationships, as well as my own experiences as an African-American developmental psychologist.

The COVID-19 pandemic has unveiled the curtain of immense inequity in our society and has had an explosive impact on Black communities nationally. In early 2021, I received my first and second doses of the revolutionary Moderna mRNA vaccine. The second time I was inoculated with the vaccine, I was one of 18 or so Black persons I counted out of several hundred people waiting hours in line for their respected dose. What puzzled me the most was that I was in the Bronx, in an area (community district 7) that is nearly 86% Black and Brown (NYCCIDI, 2019). As I waited in line, I kept asking, “Why am I one of the few Black or Brown people in this line?” Black Americans are 1.4 times more likely overall to contract covid-19 than their white peers, and those between the ages of 35 and 44 are ten times more likely to die (Reeves et al., 2020).

The release of highly effective (>94%) vaccine treatments approved by the FDA served as an early glimpse of hope as our nation entered nearly a year battling COVID-19. However, in NYC, for example, whites are receiving the vaccine at five times the rate of Black New Yorkers (NYC DHMH, 2021). Structural racism coupled with scientific mistrust rooted in historical trauma in the Black community is working in tandem to kill Black bodies here in NYC and across the nation. The writing of this paper has collided with my own experience as an African American navigating the issue of access to the vaccine and professional experiences of how one might create an intervention to address what seems to be one of the most significant barriers to increasing Black vaccination rates, and subsequently hospitalizations and death; the deeply rooted scientific research mistrust in our community. Much of these issues related to vaccine hesitancy in the African American community are rooted in centuries of historical trauma and exploitation in the name of scientific advancement.

At this moment, we are at a crossroads in research science, where we must decide to rebuke the violent and exploitative past embedded in much of the instruments, theories, and practices of our respected sub-disciplines psychology included. This paper argues that the field must address historical violence in research science and the “objectivity” or “colorblindness” of the current psychological codes of ethics and methodological practices towards Black and Indigenous populations. It is paramount that these issues are understood and subsequently addressed. Modern Western scientific inquiry’s centuries-long history of exploitation and violence towards non-whites, specifically Black and indigenous populations, have been inextricably tied to the rise and fall of colonial imperialism, slavery in the Americas, white supremacy, and capitalism. From this legacy of knowledge production, contemporary scholarship has been forced to confront given the current social, political, and scientific crises coinciding over the past year. I begin this paper by analyzing the dangers of scientific objectivity in ethical guidelines and its connection to colorblindness, building upon Teo’s (2015) critique. This is followed by an examination of the roles of capitalism, exploitation, and conflicts of research interest. Next, I explore the methodological violence of qualitative research. Finally, I present suggestions to the field in combating the violent racial history of research science.

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions.” – Proverb.

The concept of objectivity in the sciences is taught from the earliest days of formal education in the US. However, the false notion that knowledge production and investigation actions are conducted in a vacuum puts the field in spaces of peril. It can have immediate negative consequences for vulnerable populations. The “objectivity” and parallel color blindness of the codes of psychological science have not just put the moral character of the discipline at risk, as Teo proclaims (2015). Still, it subsequently weakens the strength of the knowledge production process and puts the field in danger as a whole. Teo asks, “What does it mean to do the right thing as a psychologist?” A simple yet complex question requires intersubjectivity. Teo addresses this by a close examination of primarily the Canadian codes, but much is applicable and correlates with the APA’s. The guiding principles are beneficence and nonmaleficence, fidelity and responsibility, integrity, justice, respect for people’s rights, and dignity. The quote that follows is from a section of Principal A: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence:

“Psychologists strive to benefit those with whom they work and not harm. In their professional actions, psychologists seek to safeguard the welfare and rights of those with whom they interact professionally and other affected persons and the welfare of an animal.” (APA, 2021)

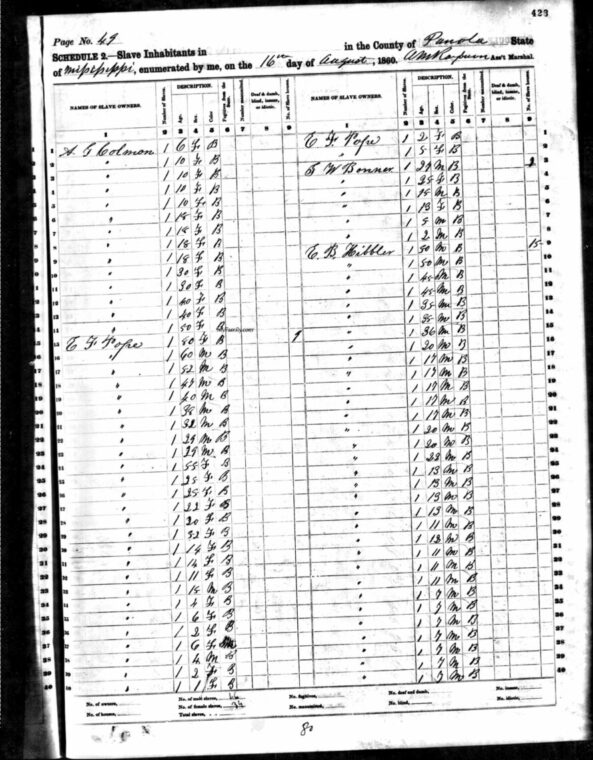

On the surface, these principles seem reasonable, but more specifically, the quote on beneficence and non-maleficence. Like all codes, this example uses a colorblind objective “do-right” language and appears applicable outside of space and time constraints. While writing this paper and doing a panel presentation on the scientific exploitation of African Americans, I was motivated to investigate my own family’s history. I traced my maternal ancestors back to my great-great-great-grandfather Sydney Hibbler and was able to identify the planter who owned him, E.B. Hibbler. Witnessing first-hand the Slave Schedule of the 1860 U.S. Census forever changed me as a psychologist of human development, but most importantly as a person. I was emotional about viewing the non-existence of my ancestor’s name. He was simply a checkmark on a legger, with sex indicated as “m” and an unknown number, to indicate he was one of the 72 persons enslaved by Hibbler. He was not a person, but property, livestock like a horse, cow, or pig. What does this narrative mean for science? As a human development student, if people have not seen my ancestors or me as completely human? What do the notions of “do no harm,” “welfare and rights” mean if the context in which the individual is operating within does not see the “other” as anything more than livestock or a subspecies of human?

Research science and our subsequent codes of ethics operate within this historical and social context. Certain racial and ethnic groups, specifically Black and Indigenous persons, were viewed on equal footing as a beast of burden, gifted by God to white men for total exploitation. The extremely dark and painful centuries-old history of scientific exploitation continues to taint Western knowledge production’s credibility in marginalized communities. One of the most poignant endless examples of this exploitation was Dr. J. Marion Sims, the father of modern gynecology. He performed countless barbaric and gruesome experimental surgeries on Black enslaved women “leased” to him from plantation owners that would eventually revolutionize the field of medicine and save the lives of many white women.

Teo’s intellectual query, “What does it mean to be a good psychologist?” or broader scientist or researcher? Many would agree to move knowledge production further along, make the world a better place, or save lives? The field must continue to ask and grapple with Teo’s inquiry, but in addition, ask the question, “But for who does this production benefit and or exclude?” Psychological epistemologies are constructed within a historical and cultural context, informing the selection of theoretical lenses, methodological practices and measures, and the interpretation of findings. Although objectivity may be the goal, there are endless spaces for biases to manifest in the knowledge production process.

Teo argues that empirical psychology has produced research that must be labeled as racist, classist, and sexist throughout its history, or what he terms “epistomoglical violence” (2015).

Epistemological violence refers to the speculative interpretations of empirical results that implicitly or explicitly construct the Other as inferior or problematic, even though alternative arrangements are available based on the same data. (Teo, 2015)

As researchers operating in this problematic context, we must ask what our role in exacerbating or being complacent in such acts of violence is? The APA code of ethics should move away from their rapid colorblindness and objectivity and directly address this mentioned violence that has existed for much of our discipline’s history. We know the dangers of implicit bias are real and have damaging ramifications for the most vulnerable populations (Goff et al., 2008, 2014). Our codes of ethics should address our epistemological responsibility explicitly when using the concepts of race, class, intelligence, gender, or difference. The APA code has several statements on “doing no harm” but no passage that refers to harm in research publications (Teo, 2015). Findings from significant studies dramatically impact public discourse and social and public policy. The codes must address precisely what do no harm means and go beyond the scope of clinical practice.

Further supporting the critique of objectivity of science, Sugarman argues utilitarian ethics codes, despite some good intentions, are oblique in addressing some of the most critical moral issues in psychology (2015). Sugarman’s piece argues that psychologists must be ideologically aware of the context in which they are operating, rooted in individualism and exploitation of others. In a similar tone as Teo, Sugarman takes a critical lens to examine the relationship between exploitation, financial incentives, research, and clinical science within psychology. The quote below from his piece describes components of this relationship.

The specific role played by Smith Kline Beecham, makers of the pharmaceutical Paxil, the preferred treatment. The timely removal of advertising restrictions permitted the company to market the drug directly to consumers. What is more significant is that the company’s multibillion-dollar marketing campaign was highly influential in linking the disorder to all manner of interpersonal and job-related problems in a way that refashioned all social discomfort as “dis-ease. (Sugarman,2015)

This complex interwoven relationship between researchers, clinicians, and corporate entities is not a new phenomenon and arguably baked into the foundation of contemporary scientific inquiry. In her book Medical Apartheid, Washington begins her work by examining these perverse relationships that started on the plantation economy of the south (2006). Physicians, industrial planters, and researchers all had similar incentives to exploit Black enslaved populations in the name of the advancement of science and economic gain.

Although much work has been done on the horrors and violence done in knowledge production in the natural sciences, few have dug deep into the roots in the hard part of the social sciences. Wertz’s (2011) examination of qualitative methods addresses such a void and closely critiques early anthropological quantitative methods. The past three decades, and the past few years specifically, have been ushered in by an era of immense social change. The rise of qualitative methods in the social sciences also runs parallel to this phenomenon. Increasingly the field is moving towards including the voices of those silenced in the past to have active votes in roles in the research process (Wertz, 2011). However, the field must reconcile with its violent methodological past and address how such problematic forms of bias may encroach into the contemporary period. Both Wertz and Washington refer to the despicable case of Ota Banga, a young man from the Belgian Congo, who was displayed at an exhibit at the Bronx Zoo monkey house in 1905 as a specimen of primitive humanity (Wertz,2011; Washington, 2006). Furthermore, Wertz goes on to point out that during the same period, sociologists focused on the process of civilizing the Native American population and acculturating urban ghetto populations of African Americans, as well as Asian and European immigrants, to the Protestant-based moral values of American society (Wertz, 2011).

For perspective, my great-grandparents, who died in the late 1990s and aided in raising me, were alive during this same period. Too often, the narrative is that these actions by researchers were done in some distant memory, in a foreign land long ago. No, these actions were done in Black, Latinx, and Indigenous communities, many of whom are still bearing the brunt of the immediate and historical trauma and the policy decisions that have perpetuated structural racism that were informed by the “science” of the day.

Psychological research science must be at the vanguard of pushing forward agendas that perpetuate equity for those Black and Indigenous communities to atone for the centuries of perpetuating epistemological violence. We must begin the hard work of rethinking our ethical codes to ensure they address these pressing issues. Psychologists must move towards a direction of knowledge production that abandons the fallacy of objectivity and colorblindness and towards one that tackles inequity head-on in a transformative way. Subsequently, the field must usher in novel methodologies that address the aforementioned historical violence and trauma and incorporate the voices and expertise of those most impacted by those actions into the knowledge production process.

It appears that no one has a comment. Very strange. Here is a question, just in case someone is interested. The critique is important, as I indicate below. But why is objectivity equated with colorblindness? The problems seem much broader to me. mike

This critique of psychological methods introduced me to a whole new literature on the problem of the false objectivity of what calls itself “psychological science.” Thanks.

I look forward to the views of other on this topic.

mike

PS- In the future it seems worthwhile to include the references with the paper. Here is what I found in tracing the work by Teo which I missed, even though the topic is up my alley. So much to read!

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/277375333_Teo_T_2015_Theoretical_psychology_A_critical-philosophical_outline_of_core_issues_In_I_Parker_Ed_Handbook_of_critical_psychology_pp117-126_New_York_Routledge

You are right, references should be added; will be added.