Introduction

My presentation responds to the concern regarding the vulnerability of local cultures exposed to dominant cultures with their assimilative tendencies. Informed by a Funds of Knowledge (FoK) approach (González, Moll & Amanti, 2005), I explore the possibility of framing such exchanges with a dominant colonizing culture in a positive way by learning to see and use the invisible competence embedded in local communities. This talk was originally presented at the Creativity and Imagination in Vygostky’s Work Seminar Series on November 29th, 2023.

The context for this study is my participation (between 2010 and 2012) as a teacher and teacher educator in a two-year afterschool English ACCESS Microscholarship Program for socioeconomically disadvantaged teens. This program was sponsored by the Regional English Language Office (RELO) of the US Embassy in India. The ACCESS program is put forth as a gateway to better educational prospects and jobs through promoting skills and knowledge in the English language and an appreciation for US culture and democratic values. The program showcases an economic prospect that attracts the partnering minority schools but also threatens to undermine their own identity and culture. However, the insidious nature of this adverse effect, as Gillian McNamee pointed out (personal communication), conceals it easily from an immediate view. Apart from the dangers of colonization, my concerns are also driven by the negative impact of a replacive curriculum, which inferiorizes the local language and culture, on the transformative learning and development of the students. This presentation, which follows the FoK approach, illustrates the significant role students’ cultural assets play in appropriating English as a useful tool while maintaining the integrity of the local language and culture.

The course of study

The local partnering school conducting the program was a culturally diverse Muslim minority institution. A hundred students were selected through an entrance test for the course from grade IX between the ages of 15 and 16. They were divided into four sections and I taught a batch of 25 students in order to learn from them for guiding the teachers on this program. I met them three times a week with each session lasting an hour and a half. Within the program’s recommended learner-centred framework, it was possible for me to extend my approach to tap into the cultural assets of the students.

Students’ community experience shaping their FoK

Deficit view of students and its negative impact

The point I want to emphasize here is that these children come to school with rich FoK, the competence they have gained in their community. They are not “empty vessels” as Freire (1970) would put it. And yet this is how they are seen by the world at large. Their teachers complain, “They [students] don’t know anything. We have to start from zero.” The ACCESS teachers formed their opinion of these students in their very first class, “How can we do learner-centered teaching with these students? They don’t open their mouth?” As their educator, these teachers challenged me with what I felt was an unjust and hasty assessment of these students. My initial efforts to involve the students in conversation were also met by their silence. Questions such as “Why do you think so?” or “How do you know that?” drew a blank. To me, this was an indication of a need to connect to them in ways that made sense to them and also help other teachers connect to them.

We construct our deficit view of students by failing to recognize their diverse but rich knowledge in school. Students’ ways of being in their community, their learning and experience there find no place in the replacive school curriculum and teaching. As a result, students lose their voice and take on the passive role assigned to them, viz. of listening to reproduce the given. As Sarason (1996, p. 362) put it simply, “Teachers ask questions and students give answers.”

Teachers tend to focus on the narrow instrumental goal of teaching to the test. In the beginning, ACCESS teachers were also anxious about the final test for certification. They seemed to miss the point that students need English as a deployable tool for communication that serves them in their study, job and life additively and not at the cost of losing their identity and rich diversity. Teachers also seem unaware of the devastating effect of their mimetic practices on students and how it silences them by erasing their “word and world” (Freire, 1970). It creates a disconnect between the knowledge and language students bring to school and school knowledge and language, making learning an alienating experience.

FoK: Promoting students’ transformative agency

On the contrary, a FoK approach affirms the learning students bring from participating in activities outside school, at home and in the community as a form of competence. This gives students a sense of identity, an opening to exercise their agency as active producers of meaning in class. Classroom becomes a meeting ground for various forms of knowledge, experience and language that students are exposed to both inside and outside school. Homi Bhabha’s (1994) notion of “third space” helps capture the new learning space that is created when students’ interests, knowledge and language are activated to work in dialectic with the dominant knowledge privileged in school. In this liminal third space school knowledge and other forms of knowledge existing in students’ communities can come together or “hybridize” and promote authentic learning that is embodied in their particularity. It is a space of possibility where the new meanings and identities students develop can disturb the “single story” (Adichie, 2009) of the dominant culture.

Creating a third space for students’ agentive learning

There is much to learn from the labor and inventiveness that goes into their work. Their work made me self-reflexive about the many careless acts we do without a thought about how it all adds up to harm the ecosystem through environmental pollution and the depletion of natural resources. This led to a very engaging project on sources of pollution in and around the community and how we could change our lifestyle and contribute in small ways to reduce our ecological footprint. For instance, a student showed me how I should hold the tap with one hand and use the other hand to rinse my face instead of letting the water run continuously by using both my hands for rinsing. I follow this rule even today as part of the resolution I made with them years ago. Another student had written that, “we must set our house in order before critisice([sic) others do.” I was very happy that the students were learning to deploy the language they were learning to express their intent. The valuable knowledge and skills in their community that could be used to learn about environmental issues and solutions formed a large part of our discussions. This project created authentic and engaging learning experiences for my students and me, while also fostering our eco-sensitivity and critical awareness. It served as a reference point for subsequent discussions on the fresh environmental issues that students brought up from their reading of newspapers.

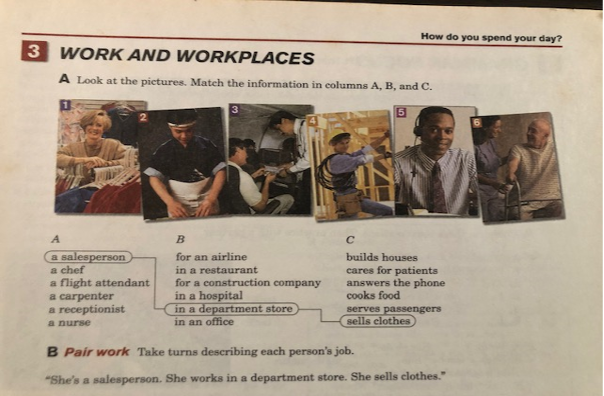

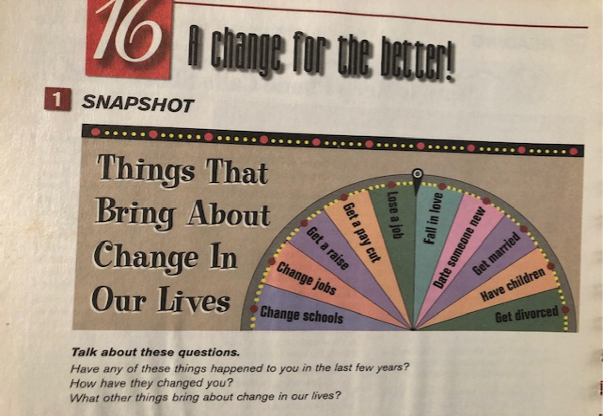

I used all the pictures we had taken as visual prompts to generate conversation about the various occupations in their community. This conversation served as a priming to introduce a unit in their textbook on work and workplaces.

Students were amused and at the same time thrilled that the material we had gathered in their community was a topic for learning in the classroom. This shared, out of class experience provided them with a meaningful foundation for engaging them in various tasks involving buddy reading:

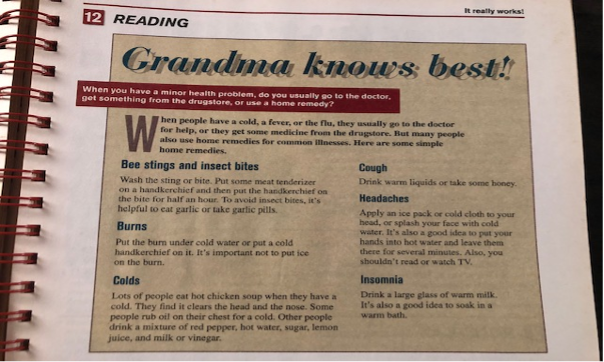

Students found this reading piece from their textbook on “grandma knows best” very interesting and enjoyable because they had a lot to contribute to this. The grandmothers hold a very venerable and authoritative place in the family and are considered as treasure troves of wisdom.

Writing:

Speaking and Listening:

Language awareness raising:

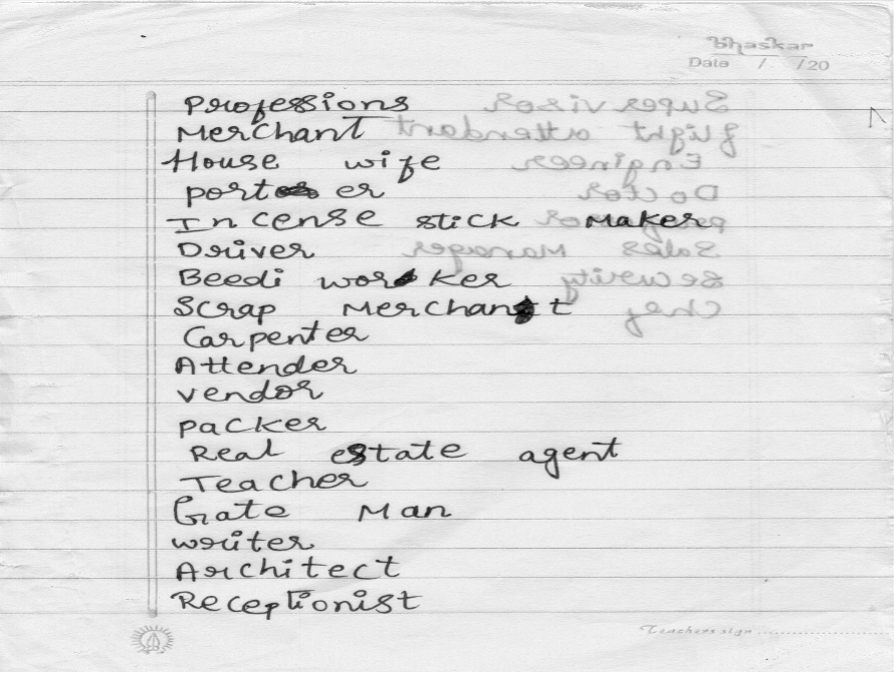

All the activities they were doing had a starting point in their culture and experience. This list of professions was a mix of what students knew and learned to name in English (e.g., porter, incense stick maker, scrap merchant, carpenter) and the unfamiliar ones they picked up from the textbook and our conversations (e.g., receptionist, architect, merchant).

A question about what the characters in the textbook they read about was preceded by what they did as you can see in the examples in the video clip:

Some reflections as an opening to dialogue

The significance of FoK seems to lie in the understanding it provides that students from diverse cultural backgrounds who we tend to consider as ‘zeros’ by school standards, have valuable knowledge and skills that they acquire from their families and communities. These funds of knowledge have an essential role in enhancing students’ transformative agency, academic performance and engagement. Another important insight is that change in individual students cannot be conceptualised in isolation except as a collective enterprise, a collective object-oriented activity involving the parents, students, teachers and the community in a shared and collaborative process of learning and development. It is, therefore, important to foster positive relationships between teachers, students, families and the community as a basis for reciprocal learning and influencing through purposeful dialogue. Empathy and respect play an important role in building trust, critical awareness and the flexibility needed to overcome the tensions and hostilities created by the social dynamics between students, parents, teachers and the community.

Each of the interacting activity systems that the students participated in the community, school, and the afterschool program was a mixed bag of resources and constraints. The creation of a third space helped set up a dialectic relationship among these activity systems enabling students to become conscious of the resources and constraints of each, question, rethink and strive to develop a more agentive stance against the colonising tendencies both within their culture, and the dominating global cultures transmitted through school and afterschool program. Within their culture, the beliefs and attitudes that students have developed in their community seem to partly limit their independent thinking. I leveraged the reading passages in their textbook to help them expand their meaning making beyond the bounds of these traditional beliefs by colliding with the independent dispositions of the characters in the book.

For example, Haseena questioned the traditional gender bias in her community that girls and women should be subordinate to boys and men. Earlier she had, resigned herself to the idea that her role as a girl was to marry and bear children. Her developing perceptions made her ask, “Why should only boys have the liberty to choose to study and not girls?” Her questioning was a driving force to exercise her agency to pursue her dream. In following her “internally persuasive discourse” (Bakhtin, 1981) she took the family along and they learned to see things from her perspective. She sees English as a language of opportunity that is serving her in fulfilling her career aspirations. However, this has not estranged her from her family or community. She is proud of her heritage, family and community. She is engaged to a boy from her community who is “less qualified” than her. She told me, “We’ll grow together.” Haseena’s case illustrates the possibility of framing the dialectic between local and global colonising cultures in a positive way that was made possible through this afterschool initiative which provided her with a third space for learning and development.

Threads of discussion and comments emanating from Haseena’s story:

References

Adichie, C. N. (2009, July). The danger of a single story [Video]. TED Conferences.

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogic imagination: Four essays by M.M. Bakhtin (M. Holquist, Ed., C. Emerson &M. Holquist, Trans.). Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Seabury.

Gonzalez, N. E., Moll, L., & Amanti, C. (Eds.) (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Bhabha, H. K. (1994). The Location of Culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sarason, S. B. (1996). Revisiting ‘The culture of the school and the problem of change’. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.